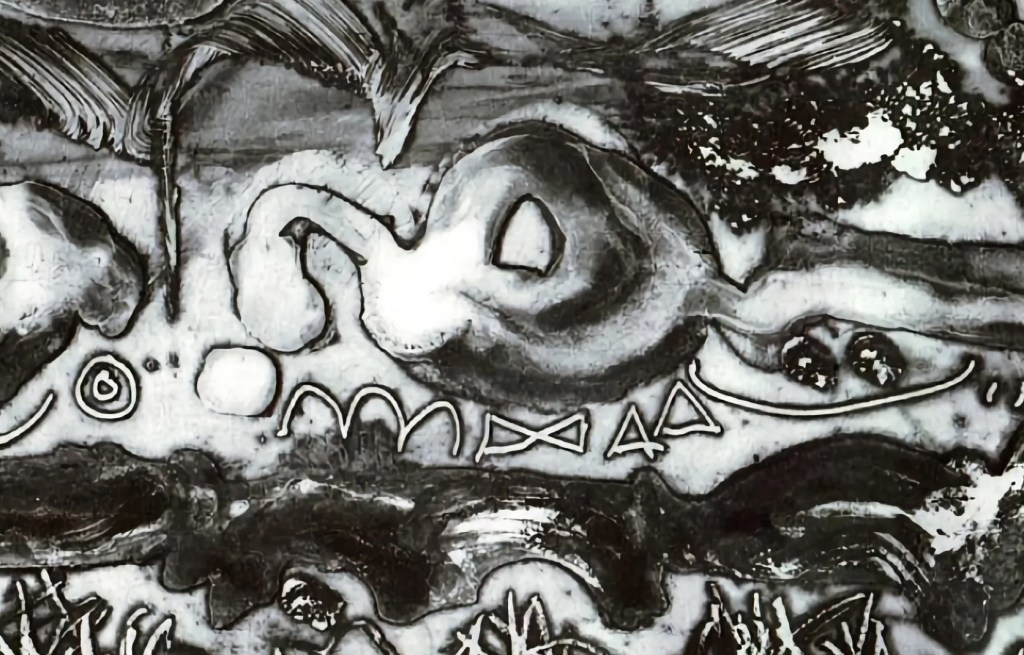

an etching printed from a Brass plate etched in Edinburgh Etch, 2000

This overview of Acrylic Resist Etching is the result of many years of research begun in the early 1990s and added to since then through continued practice and investigation. Key sections have appeared in a number of publications and periodicals and extracts were regularly reproduced as workshop worksheets. It is reproduced here in full for the first time.

This free online manual, started in 1994, gives an extensive overview of the intaglio medium

from a contemporary perspective. It is as yet unfinished, but methods have been refined, perfected and enhanced each year since the 1990s. Best us this text alongside our individual pages on intaglio, especially Hard and Soft Ground, the Beginners Compendium, and the Etching and Intaglio Type sections. Or consult some of the excellent Books on the subject.

These sources may provide additional up-to-date information and advice on current

research, methods and materials. For reference please quote this source,

(nontoxic-print.com), and its origins.

Artist website (click)

© Friedhard Kiekeben, 1994 – 2025

edited by Jennifer Helen Shaw,

many thanks to Keith Howard for his vision and support

Acrylic Resist and Innovative Etching: Metals

When I began writing about nontoxic printmaking methods they were still relatively unexplored, except by a few dedicated and innovative individuals and institutes. Since then new ideas, materials and processes have emerged or been refined. The body of this manual remains valid and, where appropriate, links have been inserted to direct readers to the most recent developments. The aim of the website will be to continue to provide useful updates.

Some thoughts on the toxicity of traditional etching

In etching a blank plate becomes the arena for creative events, for the incision and alteration of the surface of the metal. This is done by various means such as scoring, scratching, scraping and of course as the term etching implies, by using corrosive chemicals to eat into the depth of the plate. The grooves, indentations, scars and scratches produced by

etching turn the once flat plane of a plate into something resembling a landscape eroded by the elements – a structure beneath the surface commonly referred to as intaglio.

The term intaglio is derived from the Latin in-tagliare meaning to cut into. The term etching is often used to describe all intaglio techniques. Strictly speaking, it should refer solely to processes that involve a corrosive action.

The more correct generic term for the broader range of incisive processes is intaglio

printmaking. Once a plate has been worked and is ready for printing it is covered with a generous deposit of ink. After wiping, just the deep recesses still hold significant amounts of ink. An etching is printed by laying the plate on the bed of an etching press, covering it with a sheet of damp paper and set of felt blankets, then running it through the two heavy steel rollers. The massive pressure exerted by the press pushes the paper firmly into the grooves of the plate where it picks up the ink. In this way, a reverse copy of the plate’s 3D topography is produced as a two dimensional image consisting of lines, textures and tonal areas.

The inking, wiping and printing processes of any intaglio plate is essentially the same, but the ways of creating the intaglio are many and various.

Historically, etching plates have been made using three types of intaglio method:

The mechanical or cold techniques such as drypoint, engraving or mezzotint where the plate is physically shaped using specially designed metalworking tools.

The etch, or hot techniques that include hard ground etching, aquatint or open bite where etchant resistant grounds are applied to the plate and exposed areas of metal are eroded by a mordant.

The less frequently used collagraph techniques where an intaglio plate is made by

building up a relief surface rather than eroding it.

And now, the new photopolymer processes represent an important extension to this

canon.

A brief historical perspective

The sculptural nature of etching finds its origins in the ornamental engraving of objects. Goldsmiths, tool and weapons makers and other craftsmen were proficient in decorating their wares using engraving techniques long before the age of mechanised printing. The first intaglio prints were reputed to have been taken from such objects. By the 16th Century the invention of the intaglio printing press enabled artists like Durer to take impressions from metal plates and intaglio work

increasingly came to be seen as the means to create a matrix for the reproduction of linear drawings.

Daniel Hopfer: Portrait of Martin Luther, 1523; The artist is credited as the inventor of etching. His impressions were printed from acid etched steel plates. Prior to Hopfer etching had been known as a technique for incising metal armor, but not as a technique in art or artistic printing.

The creation of an image on a plate using mordants and resistant grounds was well known to master engravers of this period but another century would pass before acid etching was widely adopted as the preferred means of producing the intaglio groove. Artists began to favour the way that etching allowed them to work much more quickly, spontaneously and with a greater range of marks than the hand held burin would permit. Rembrandt with his unrivalled intaglio work would firmly establish etching as a supreme medium of artistic expression capable of conjuring up exquisite imagery full of life, depth and vibrancy.

The artistic excellence that Rembrandt achieved should, however, be appreciated in conjunction with his ceaseless exploration of new technical possibilities. He experimented with different mordants, etching tools, etch resistant materials

and printmaking papers; he even designed his own wooden etching press. Any enthusiast for the art of intaglio printmaking would be well advised to visit Rembrandt’s house in Amsterdam which gives a vivid impression of the master’s working practice. Although Rembrandt’s aesthetic genius has inspired generations of printmakers, his spirit of inventiveness seems to have been somewhat less influential. Many have been content with the end result – the fluid, linear drawing – without the urge to continue to explore the means of production.

Over time, various mechanical stippling and mezzotinting methods were devised to give a degree of tonal quality to intaglio prints but it was not until Jean Baptiste Le Prince invented the technique of aquatint in the middle of the 18th Century that etching acquired a much more satisfactory painterly process. Le Prince discovered that a fine dust of rosin particles melted onto a metal plate became acid resistant, enabling the artist to set down areas of granular dots that would appear as luminous tones on the print. Many painters were intrigued by the new method. Francisco de Goya, in particular, made extensive use of the technique, taking it to levels of virtuosity that have rarely been equalled. The 18th Century also brought the introduction of the soft ground or vernis mous method, first used in France to emulate the textural qualities of crayon marks in an intaglio print. This further extension of the mark making vocabulary was quickly embraced by artists across Europe. By now, a sufficient arsenal of methods was available for commercial printmakers to be able to produce faithful intaglio reproductions of paintings.

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal.[1] In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types of material. As a method of printmaking, it is, along with engraving, the most important technique for old master prints, and remains in wide use today. In a number of modern variants such as microfabrication etching and photochemical milling, it is a crucial technique in modern technology, including circuit boards.

(WIKIPEDIA)

The photographic revolution

At the very beginnings of photography, in the early 19th Century, the photo sensitised etching plate was considered a serious contender to the silver-emulsion based systems that are in use to this day. Photo etching, commonly known as photogravure or helio gravure, as a viable artistic and industrial process was devised by Karl Klic. His process is the foundation of rotational intaglio printing which is used for the production of high volume print runs such as glossy magazines. Sadly, the photo-reprographic potential of the intaglio medium was not exploited by most artists working in the first half of the 20th Century. With a few exceptions, rather than investigate new possibilities, most seemed content with proven and tested methods. In general intaglio printmakers were content to continue with the established methods rather than be at the forefront of new developments.

A kind of conservatism started to prevail in both technical and pictorial terms and although many great 20th Century artists have produced interesting intaglio work, often under the auspices of master printers, the emphasis has been on commercial reproduction. Few artists used the medium as their main form of expression. Stanley William Hayter, with his rejuvenation of engraving and development of intaglio color printing is perhaps the one exception. Moving in illustrious circles that included Picasso and Miro he promoted a climate of sharing and accessible working practices in which no trade secrets were to be kept – an approach that stands as an example of good practice for today’s printmaking community.

In the 1960s, printmaking experienced something of a renaissance, but mainly in the new medium of screenprinting. This new method captured the spirit of the time as it offered the aesthetic of the emerging pop and media culture with ease of execution. Warhol’s soup cans were screenprints, not etchings. Intaglio had lost touch with the avant-garde and was increasingly seen as traditionalist and craft orientated. An increasing awareness of environmental and health related issues didn’t help the popularity of etching either. Artists and students were favouring safer, simpler, more modern-looking modes of printmaking.

Etching today

In the eighties I was fortunate to be taught by an enthusiast of intaglio printmaking. At the time etching was still in something of a general decline, not only in Germany but also across most of Europe. I discovered that the medium could be contemporary and to my delight found that it continued to flourish in the UK in an abundance of open access, editioning and college workshops. Thankfully, etching now seems to be shaking off its old fashioned image and many artists are once again investigating the technical possibilities and exciting new aesthetics in a new era of intaglio printmaking. Thanks to the pioneering efforts of artist-innovators such as Keith Howard, today a new intaglio system has become available. Acrylic Resist Etching introduces a whole new range of technical and creative possibilities whilst being much safer and easier to practice than traditional etching. In aesthetic and conceptual terms there is also a sense that intaglio printmaking can once again become an innovative and relevant medium. Notions of reproduction and simulation and digital technology are defining the current age and its image making. Printmaking has always enjoyed a natural affinity with the mechanics of each age. Matrix, copy, reproduction, encoding, simulation are all familiar terms and any etched metal plate is as much a repository of condensed information as a computer disk. The use of digital working methods in conjunction with the depth, tactility and sumptuous sensuality that is the special hallmark of intaglio printmaking offers a rich field of contemporary artistic investigation and production.

The dangers of traditional printmaking

The amazingly rich and varied art of intaglio has, historically, come at a price. The traditional methods used by many artists and workshops to the present day involve a cocktail of toxic, harmful and potentially dangerous chemicals and processes unrivalled by most other artistic disciplines. Each ingredient can in itself have a damaging effect on the health of the artist; but used in conjunction with each other, they present a very serious threat to those practising printmaking on a regular basis.

In chemical terms, by the 19th Century, intaglio printmaking had been built on hazardous foundations: Firstly, in its reliance on an ever increasing range of oil-based materials used as acid resists, substances such as asphaltum, bitumen, modified waxes, rosin dusts and shellac varnishes.

Secondly, intaglio had come to make extensive use of a variety of volatile organic solvents, starting with distilled turpentine in earlier times and graduating to synthetic hydrocarbon compounds around 1850 when modern chemistry was established.

The third component of this type of printmaking was the use of strong acids such as nitric acid, hydrochloric acid and acetic acid. A casual awareness of possible health risks existed even in centuries past but it is only in more recent times that hazards have been fully understood and only very recently that improvements have been made to the practices of intaglio printmaking and genuinely workable alternative methods proposed.

Hooked on Solvents?

The traditional intaglio system is essentially oil-based. Most of the acid resistant grounds and materials are petrochemical products such as asphaltum varnishes, shellac, mixes of tar and wax, resins and so forth. A great number of these materials are proven carcinogens. Many contain organic solvents – also known as hydrocarbons – that give them the required properties but which also quickly escape into the workshop atmosphere during use. Ironically, the solvents prevalent today cannot have been, as sometimes asserted by traditionalists, an essential part of the established intaglio repertoire because they are the products of relatively recent chemical development. It is in fact quite likely that Rembrandt and his contemporaries used a range of cleaning agents such as Marseilles soap made from olive oil and other non-volatile solvents. These are much safer than the aromatic hydrocarbon solvents heavily promoted by the petrochemical industry.

Short-term exposure to these solvents often causes headaches and nausea (the body’s first warning signs!) and prolonged contact can lead to damage of the liver, kidneys and nervous system. Typically this is accompanied by a reduction in the body’s production of blood cells which translates into a weakening of the immune system. Organic solvents are not only contained in the oil-based varnishes, they are also in constant use in the traditional print studio in the removal of varnishes and the cleaning of plates after printing. Hydrocarbon solvents such as white spirit can easily enter the body through inhalation and absorption through the skin. Strict safety precautions such as the use of gloves, respirators and fume extractors should be observed when using these materials but very often sufficient measures are not taken. In shared workshops and educational environments, the level of protection required can be difficult to achieve and maintain. The enforcement of more strict regulations in Europe and elsewhere marks a great change from the laissez-faire attitude of the past – any contamination of the water supply with solvents can be prosecuted and solvent-based products must now carry drastic health warnings like those found on cigarette packets. As a result of the measures, white spirit sold in the UK for DIY has acquired a warning that pneumonia and lung damage may result from the use of this chemical.

Another major threat to the health of the traditional printmaker comes from the use of various acids. The most common of these, nitric acid, used to be popular with many etchers as it erodes a range of metals very quickly (even though its biting action can be erratic and somewhat coarse). Nitric is a very strong acid in its most corrosive neat form. Inhalation of strong nitric fumes can lead to eye damage and pneumonia; it can even be fatal. The nitrogen dioxide gas emitted during biting can lead to reduction in the blood oxygen carrying capacity, chronic lung disorders and death. Nitrous fumes can also cause damage to the reproductive system i.e. birth defects, impotence and alarmingly, in conjunction with chlorine based

cleaning products, can even produce mustard gas! Surprisingly perhaps, the hazards of intaglio printmaking are by no means a recent discovery. In the early days of the medium it was common practice to pour nitric acid over the metal plate until the grooves were deep enough. This extreme exposure commonly caused impotence, a condition which is reputed to have been called the etcher’s disease in mediaeval Germany.

Due to new health and safety regulations the use of nitric acid in industry is now subjected to strict safety measures. A metal finishing company in the UK was instructed that nitric may only be used in fully enclosed and sealed glove boxes of the type used in the processing of radioactive material. This company, like many others, subsequently invested in etching facilities using ferric chloride as a safe alternative.

In addition to health risks there are also a number of safety hazards connected with traditional etching materials and processes. The dust particles of a traditionally used resin aquatint are known to be highly explosive (as well as proven to irreversibly clog up lung tissue). The use of a gas flame to melt the resin onto the plate could hardly be called safe practice. There are numerous documented cases of fire and explosions in etching workshops which were a result of the inherent fire hazard of resin aquatint. Plate smoking, solvent fumes, hot plates and oil-based inks and varnishes present similar fire hazards. The reader might be wondering;

Aren’t these just worst-case scenarios?

These materials have been used for centuries, surely they must be OK for me to use?

Is there really any evidence of damaging effects? Sadly, the medical evidence is compelling. There are documented cases of impaired vision and pneumonia as a result of contact with acid fumes; instances of nerve damage due to long-term solvent exposure; birth defects in offspring etc. Like many professional printmakers I personally know of a number of colleagues whose health has seriously suffered as a result of long-term exposure to toxins. I myself often experienced headaches when I was still practising traditional etching. I developed allergies to many oil-based chemicals and experience a severe bout of conjunctivitis while working with nitric acid.

So why is it that despite the profound risks, so many artists have worked in the intaglio medium when they could have opted for safer means of expression? The answer is simple. Artists who were fascinated by the creative possibilities of intaglio printmaking had to make do with the oil-based system due to the absence of a viable alternative. Perhaps there is also a romantic – if irrational – attraction to the mastery of a practice involving mysterious and dangerous substances and processes. No one could have expressed this appeal better than William Blake in the famous passage from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell;

If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is

infinite … This I shall do by printing in the infernal method by corrosives … melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid.

The attitude towards toxic process has now shifted from a policy of hazard management to one of hazard avoidance. Instead of trying to contain and control high-risk processes, the new move is to use methods and materials that present much less risk to begin with. This change of approach is easily achievable in practical terms. However, change cannot only be a simple technical shift. It also necessitates a shift in the attitude of printmakers, some of whom feel a devil-may-care affection for the old alchemical ways even though they are no longer justifiable by necessity.

It is hard to give up smoking!

Some may say that Health & Safety restrictions are choking the life out of the practice of etching. Not at all! A progressive etching workshop does not need to use any of the kind of volatile chemicals we have been discussing. Modern alternatives have become available which can deliver the same end results, are a lot safer and even open up exciting new creative possibilities. This research sets out to demonstrate that the new techniques are just as suited to Blake’s romantic quest to reveal the infinite beneath the surface as the corrosive ones that preceded them.

For more information about printmaking hazards click on the following links:

Health + Safety The Toxicity of Solvents

Metals used in Etching

Copper, Brass, Zinc, Steel, Aluminum

The most common metals used for intaglio printmaking purposes are steel, copper, zinc and aluminum. These different kinds of metal can be equally stimulating to the artist’s imagination as they each offer quite distinctive mark-making possibilities.

Plates suitable for etching can be obtained from professional printmaking suppliers, most of which have a range of good quality metal plates in popular sizes; or from sheet metal dealers who will be listed in local directories and on the web. If you are planning to do quite a lot of etching the local dealer is by far the cheaper option.

Metal plates of 0.8mm to 1.5mm thickness are recommended for intaglio printing. If the thickness is described in gauge this equates to a range from about 20 to 16 gauge: remember that the higher the gauge number the thinner the plate. If plates are thinner than recommended they can become awkward to wipe and are unsuitable for long etches. Plates thicker than 1.5mm should not be used as they can easily damage paper and blankets during printing. As metal is sold by weight a thicker plate will also be more expensive and more difficult to cut. However, a heavier plate does have a more tactile and object-like quality if you are looking for a more sculptural approach to etching.

With acrylic based etching it is not essential to buy the most expensive kind of highly polished plate so long as you make sure that there are no deep scratches or corroded patches on the metal. Any minor scratches and blemishes will be removed as part of the plate preparation process and deeper grooves can be levelled out with a scraper or sander before

preparing the plate.

NOTE: In contemporary intaglio printmaking, non-metallic plates such as sheets of plexi, PETG, or other sheet materials are now also being used for drypoint etching and monoprinting and as the substrate for photopolymer film.

Etch Copper and Brass (The Edinburgh Etch)

Copper has traditionally been the preferred metal for etchers as it facilitates an extremely detailed and accurate intaglio reproduction of lines and other marks. Copper plates are hard enough to withstand editions of thirty prints or more without significant wear but if very delicate mark-making techniques are employed (such as aquatint or drypoint) or if a much higher number of prints is required, it is advisable to have the plate steel-faced; an electrolytic process that can be carried out by some professional print studios. Copper will print most colored etching inks without discoloration, but again, steel-facing would be necessary to guarantee perfect results. Copper is suitable for all intaglio techniques; ideal for both linear

and tonal work, and in open bite the eroded areas remain as smooth as the plate surface.

If you buy the reddish copper plates from a sheet metal dealer they should be labelled half hard cold rolled. Never buy hot rolled kinds of metal as they are hardened and very difficult to etch. In some cases the rolling texture of the metal can appear as parallel lines during etching, but this tends to be more common with zinc plates, very rarely with copper and does not occur at all with steel plates. If a totally uniform plate is required (e.g. for engraving) it may be worth investing in hand-hammered plates that are still available from some printmaking suppliers.

When working with copper, bear in mind that this metal wants to be guided into shape by the artist. Its temperament is precise and delicate, so if it is to reveal its more powerful side it should be encouraged by appropriate means such as multiple etches, drypoint etc. If treated in this way a copper plate can convey a whole symphony of marks, textures and tone as was so masterfully demonstrated by Rembrandt.

Etching Brass (The Edinburgh Etch)

Brass is a superbly suitable material for intaglio etching and printing. The metal has a golden, mirror-like finish, and usually lacks the more or less pronounced rolling texture of other sheet metals. It is often supplied by the same sheet metal merchants that sell copper and is only marginally more expensive. The Edinburgh Etch method now allows for this noble metal amalgam to be etched as easily as a sheet of copper. Arguably, brass surpasses any other metal in terms of its versatility of marks, its faithfulness to etched detail, and its overall aesthetic expressiveness.

Brass can be etched in the same solution as the one described for the Edinburgh Etch for copper. The golden aesthetic of this very hard alloy of zinc and copper combines the delicacy of copper intaglio with the robustness of etched steel; due to their hardness, plates do not suffer from wear in large editions. Brass plates yield unique textured effects in conjunction with the various acrylic wash and open bite processes, for instance when a combined Speedball screen filler and carborundum wash medium is used as an etching resist.

Zinc Etch Zinc, Steel, Aluminum (The Saline Sulfate Etch)

Another popular kind of metal used in etching is the silvery looking zinc. Even though zinc does not conjure up alchemical connotations quite like copper and is mainly known in the practical world of building and plumbing, it is a very good material for intaglio printmaking. There are several factors that commend this often underestimated material to the etcher.

Due to its predominantly mundane application, zinc is usually a lot cheaper to buy than copper. But zinc has creative as well as cost benefits. As it is more impure than copper, zinc reacts with other substances more easily and more vigorously, a characteristic which can be exploited for etching purposes. Zinc has a crystalline texture and when etched the bitten surfaces will bear a certain roughness that produces tone on the print. As the zinc oxide deposit producing this tone gradually wears off during printing it is advisable to use aquatint when tonal areas are desired.

The Saline Sulfate Etch now allows a greater crispness and evenness of bite on zinc, something normally only associated with copper. So the lines and indentations etched into zinc can on one hand be rendered as delicate and precise as on copper or the etch process can be manipulated in such a way that the marks produced are rugged along the edges.

Deeply etched intaglio areas for dark expressive areas on the print or heavy embossing are easily achieved on zinc plates. Zinc is the most malleable metal suitable for intaglio work. This means that all mechanical processes such as drypoint, scraping, burnishing and so forth can be executed with great ease. The disadvantage of this material’s softness lies in the fact that the tremendous pressure of the etching press can flatten delicate areas of the plate – especially drypoint, aquatint or mezzotint – after a number of prints have been taken. The wear of zinc is sometimes exaggerated however, most plates would yield at least 10-20 successful prints and whilst editioning is considered an advantage of the intaglio medium, many

artists are quite happy to explore the potential of a plate in a number of good artist proofs without ever using the zinc plate for mass production. As most kinds of zinc on the market are actually an amalgam rather than the pure element its durability will vary. Plates that are manufactured for the printing industry have a finer grain and are much harder than the plumbing zinc and also come with a mordant resistant backing. Zinc is not ideal for color printing as it can alter the appearance of some etching inks, especially yellows and bright colors. However, too much emphasis is sometimes placed on this and many etchers successfully print with a wide range of inks from zinc plates with negligible contamination. Zinc can be used for all acrylic resist etching techniques and it lends itself to large-scale work as the plates etch best in trays.

Steel Etch Zinc, Steel, Aluminum (The Saline Sulfate Etch)

Etchings taken from steel plates tend to be somewhat more expressive in nature than those taken from copper or zinc. The reason for this lies in the fabric of the material. A steel surface, even if highly polished, has a fairly coarse and granular crystalline structure.

The porousness that characterises steel makes it particularly well suited for intaglio printmaking as the main idea behind etching is to create surfaces that are capable of holding ink deposits. Etchings printed from steel hardly ever look faint or lacking in definition, and if required, a plate tone can be left on the surface giving a richness which is unsurpassed by any other plate metal. Despite its eagerness to absorb ink and transfer it to paper, steel plates which have been burnished are also able to produce white backgrounds, which is why it is the preferred material in industrial intaglio printing. Even today, bank notes and stamps are printed from steel plates.

Steel is the ideal metal for color printing as it has no contaminating effect on any kind of etching ink and as its industrial use suggests, its hardness also makes it the ideal choice for editioning. Literally hundreds of prints can be taken from the same steel plate without any significant wear and even those techniques that produce a mark by means of a raised burr such as drypoint can safely be employed for editioning.

Any mechanical and abrasive work done on a steel plate by firm scratching, scraping, incising etc. will produce lines and textures of great vigour and density. It demands a certain decisiveness from the artist but steel is equally capable of yielding painterly effects. Unlike other metals, steel will by itself provide a tonal quality when exposed to the action of an etch solution. This tone which, contrary to zinc, is not caused by a deposit but is actually etched into the metal itself, will increase with the length and depth of the bite. An open area etched on a steel plate will not appear as a light patch with an outline as with copper, but as a dark patch that stands up as a positive mark by itself. The tonality can be enhanced with aquatint. If, however, a very fine spectrum of greys through to the richest black is required, then copper is still the best choice of metal.

Steel is one of the most common metals used in construction and engineering which means that sheets of steel can be obtained easily from most local sheet metal dealers. It is important to ask for cold rolled mild steel which usually has a slate grey, sometimes reddish, tinge and a coarser surface than zinc. The plates available today do not consist of pure iron but, as the term steel suggests, are iron with a carbon content. If by chance you have obtained hardened varieties of steel (such as hot rolled) the increased carbon content will make satisfactory etching impossible. Also, be careful not to purchase plates which are excessively scratched or rusty – it is best to ask for plates that are cold reduced, meaning that they have been coated with a protective layer of grease.

Steel can be used very successfully for most acrylic resist etching techniques, but in the application of the different grounds, the porousness of the metal has to be taken into account, necessitating a thicker deposit of acrylic varnish. As with zinc, the Saline Sulfate Etch is best for steel. It is well suited to large scale work.

Aluminum Etch Zinc, Steel, Aluminum (The Saline Sulfate Etch)

Due to its softness and its coarse atomic structure, aluminum is somewhat less suited for the entire spectrum of intaglio printmaking than other kinds of metal. However, since plates are cheaply available from sheet metal merchants (you may even get them for free from commercial printers) many printmakers use them for straight dypoint work or as a substrate for

photopolymer work. Previously, this lightweight metal was rarely used for intaglio etching; but now, by using the Saline Sulfate Etch, it provides unique benefits and qualities. In etching, aquatint is normally used to fill open areas on the plate with durable tones or a black. The Saline Sulfate Etch for aluminum is self-aquatinting. During etching a very distinctive and durable surface roughness occurs in the open areas, this crystalline texture can produce a beautiful black on the print all by itself. As a result, there is no such thing as open bite in this process since all etched areas become carriers for etching ink, thus enhancing the graphic potential of the process.

Unusually, neither of the basic components of the Saline Sulfate Etch, i.e. copper sulfate and salt, have any corrosive effect on the metal by themselves. But etching becomes possible when both substances act on the metal in combination. While all other metals easily erode as long as they are grease free, the surface of aluminum plates is best treated with fine wire wool to make the surface more susceptible to the etching process. This should be done before any acrylic grounds are applied to the plate.

As with the zinc process, the Saline Sulfate Etch for aluminum involves the production of a very loose coppery sediment which floats to the surface and should be removed regularly. However, the continuous rising of small hydrogen bubbles also indicates that etching is in progress (these are not considered a hazard).

Tip: When stripping acrylics off an etched aluminum plate, ensure that plates are not

left in the soda ash stripping solution too long as this will etch the plate further.

Spelling Note

USA Aluminum

UK Aluminium

The different etch techniques of acrylic based etching can produce very different kinds of marks and effects when used on copper, brass, zinc, steel or aluminum. It is well worth the effort investigating these possibilities to gain a varied aesthetic repertoire which can then be deployed for any etching project.