Safety Aspects of Photography in the Digital Age

Traditional Darkroom Processing / ‘Alternative’ Photography and Cyanotype

35mm SLR camera B+W Enlarger (Paterson)

sources: Kiekeben (edit) | M. McCann, PhD | Center for Safety in The Arts | Spandorfer | Wikipedia

Photography now looks back at nearly 200 years of development. The lens-based medium has

taken the world by storm and

Joseph Nettis: ‘Spanish Woman’, 1957, gelatin silver print.

The artist was concerned about chemical fumes and installed extensive ventilation in his darkroom. ‘I also don’t use toners or other exotica’.

“After National Geographic published photos from his bicycle trip through Europe in 1955, he persuaded the magazine to sponsor a round-the-world journey in the spring of 1956. What originally was to be a three-month trip lasted more than a year. Mr. Nettis traveled mainly by scooter, mostly sleeping in people’s homes, though he slept in a monastery and in a jail in Japan.” (Philly.com). After completing his work for National Geographic, he struck out across Spain, where he shot 10,000 photos for a book he eventually

published, A Spanish Summer.

Photographic Processing Hazards: Overview

Photo Processing Hazards in Schools

The National Press Photographers Association Health Survey fundamentally changed the way we picture things.

Over the years a multitude of chemicals and emulsions with photographic uses and light sensitive properties were discovered – ranging from relatively harmless silver halide compounds to extremely hazardous substances; various heavy metal salts and even uranium and other radioactive agents were found in the toolkits of early photographers.

The transition to digital processes is now nearly complete, and traditional film photography has become a niche market. Darkroom processes are still taught at art schools to convey a sense of historical continuity to today’s tech-savvy students.

A stable molecule under room temperature conditions, this compound is known to be able to release toxic hydrogen cyanide gases when exposed to heat, UV radiation, or in the presence of strong acids.

The US safety agencies EPA, NIOSH, and the CDC have documented numerous cases of serious toxic exposure cases involving a Cyanotype chemistry used by artists and in textile art.

1). a case from 1979, in excerpts:

https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/hhe/reports/pdfs/81- 171-880.pdf

“The artist reported mucous membrane irritation; burning and itching sensations on her arms, face and hands; facial and finger edema, difficulty focusing eyes, sore mouth and anus, headache and nausea, which were temporally associated with the cyanotype printing process itself or contact with fabrics which had undergone the cyanotype process. The artist had not performed the process since the summer of 1979. However, she continued to report symptoms when utilizing fabrics which had been previously treated. She was also concerned about potential contamination of her work area and residence.”

“The artist reported that she had first begun the cyanotype process in June 1978. She noticed a tingling in her hands and skin during the measurement of chemicals, and acute flareups of symptoms each time she engaged in the process. She discontinued use of the process in the summer of 1979. The symptoms, however, would recur from time to time. By careful observation the artist was able to link her symptoms to contact with materials which were directly or indirectly involved in the cyanotype process. The symptoms abated when she was away from home, providing she did not bring any of the treated cloth with her. The symptoms were most severe during hand stitching of the fabric into a quilt, during which time there was extensive skin contact with the cloth and some oral contact due to threading of needles, knotting of threads, etc. Occasional accidental needle pricks to the fingers also.”

2.) a case from 1992 (abstract)

https://hero.epa.gov/hero/index.cfm/reference/ details/reference_id/1237280

‘Alternative’ or Historical Photography

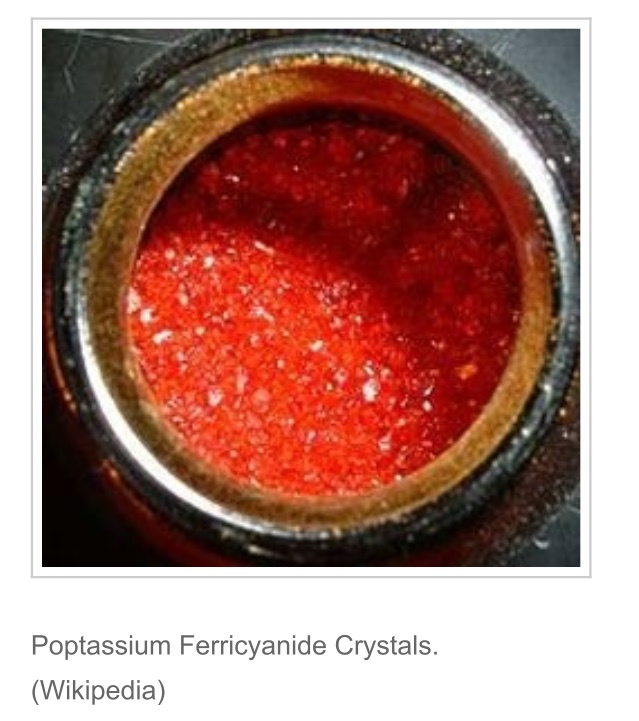

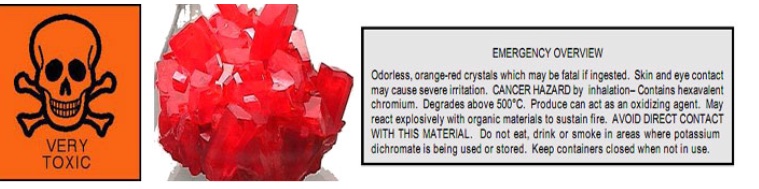

Potassium Bichromate, the widely used staple ingredient of Alternative Photography is highly toxic and is known to cause cancer

Potassium Ferricyanide, the main ingredient in Cyanotype printing is now used in large quantities by artists and in art schools. A common misconception, also supported by some chemists, suggests ferricyanide to be a harmless compound. Members of the art safety / industrial hygiene community have long contested this claim, (and warn against potential cyanide gas release due to to UV exposure, heat, or acid). Both the US agencies EPA and CDC have argued against the

widespread use of the Cyanotype process since the late 1980s.

The rise of the digital age has also brought about a movement that tries to reconnect with early photographic means, chemicals and methods known as Alternative or Historical Photography, and many of these authentic processes yield outstanding photographic images.

Unfortunately, most of the historical processes are in a special league of toxicity.

While many of the harmful substances of printmaking are in the toxicological class of ‘toxins’ (known more to cause medium or long term health effects, but not necessarily presenting immediate danger) many of the agents utilized in Alternative Photography are outright ‘poisons’ capable of harming or killing a person

through ingestion or vapor inhalation.

A few decades ago there was still a debate if the widely used ‘bichromate’ (sodium or potassium bichromate, chromic acid, also known as ‘dichromate’) was toxic but now there is undisputed evidence that the chromium salts are highly toxic and are classed as ‘poisons’; chromium salts have also be found to be highly carcinogenic. The casual attitude in the use of this highly reactive chemical amongst some users, schools, and photographers is of concern. Hazardous materials such as this should only be used with the most stringent precautions, and in our view, safer alternatives should be sought out as much as possible, especially in an educational setting.

The health hazards involved in making handmade quilts involving a cyanotype printing process were evaluated. An artist engaged in creation of handmade quilts in her residence had experienced facial and finger edema, mucous membrane irritation, headaches, and nausea, was investigated.

The cyanotype process was used to transfer photographic prints to fabric, which was later incorporated in quilts. Chemicals used in the cyanotype process included potassium- dichromate (7778509), which is known to be highly toxic and a skin sensitizer. Even though the artist had discontinued use of the process, symptoms recurred when she handled or sewed cloth treated with the cyanotype process.

Work surfaces tested positive for contamination with hexavalent chromium (CrVI). Air and vacuum sampling indicated that CrVI was not present at detectable levels. The author recommended discontinuing the use of the cyanotype process, or discontinue use of potassium-dichromate as fixative, decontaminating the basement with soap and water, washing fabrics thoroughly in hot water, and avoiding contact with other sources of chromates.

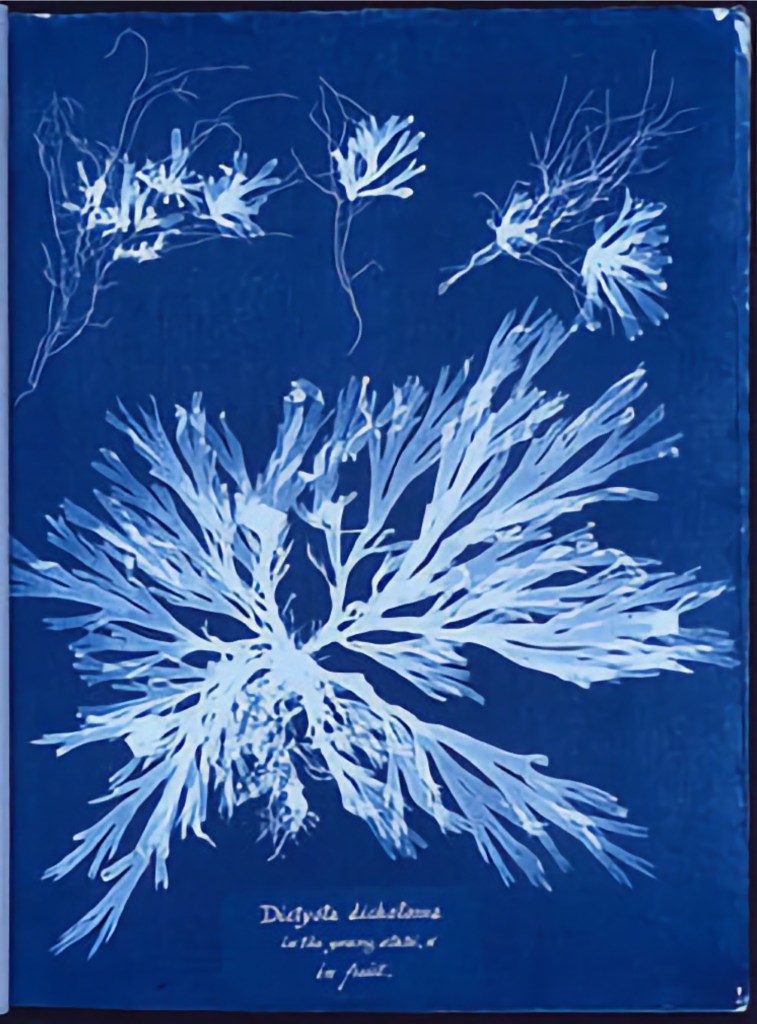

Cyanotype or Blueprinting

The popular process of Cyanotype is widely believed to be a fascinating and harmless photographic curiosity. Various books and websites helped popularize the method amongst artists, hobbyists, and in art schools in recent years, and brought about a Renaissance. The artist’s variety of cyanide compounds is based on a more hazardous molecule than the ‘architect’s blueprint’ or the blue pigment. These are separate processes.

The English botanist Anna Atkins, born 1799, is regarded as the first female photographer. She also pioneered the art of the photogram. ‘Cyanotype: Algae’ (Wikipedia)

The hidden dangers of Cyanotype

The deep blue prints made in Cyanotype are very alluring, but on reflection, the chemical hazards that are present (both in the process and in the prints) may outweigh the aesthetic benefits.

The key compound needed in Cyanotype chemistry – potassium ferrocyanide – is falsely thought of as safe. Many think of this common iron salt as harmless because it can safely be ingested.

The US food agency (FDA) declared the chemical safe in the 30s, based on knowledge available at the time. Yet on contact with UV light or acids, or heated to mid-summer temperatures the compound can break down and release hydrogen cyanide gas (HCN) that can be as toxic as nerve gas. Ferrocyanide has even been implicated in terrorism (Rome).

Ferrocyanide is not to be confused with the iron cyanide molecule of its relative Prussian Blue (or the printing ink Cyan) which has a very stable and much more inert chemical structure. The nontoxic compound is used in ink, paint, and pigment making, and in certain medications. Only experts can fully explain the subtle but highly significant differences between the various blue cyanides that are used for these different applications.

The professional use of small amounts of ferrocyanide in the food industry and for medical applications may not be of concern. However, it is questionable if amateurs should be advised to use dry ferrocyanide powders or bottled cyanotype formulations as a staple ingredient in their practice.

Making photographic prints and decorated fabrics with the Cyanotype process, and the reactive chemistry it entails, carries very significant risks.

The EPA reported a case where an unsuspecting amateur photographer made printed quilts treated with cyanotype chemicals as a hobby, and then suffered permanent facial injuries as a result of what was believed to be possible exposure to cyanide vapors and/or chromium compounds. The EPA warns: ‘…the hexacyanoferrates used in cyanotype, blue print, and in Prussian blue pigment should be considered true cyanides.’ (see pdf below)

Can Cyanotype Practice kill Fish?

Recent Findings show that Potassium Ferricyanide (Cyanotype Powder), is highly toxic to fish, a fact that is rarely mentioned in the ‘how-to’ literature on this process.

(excerpt – Researchgate)

Toxicity of Ferro- and Ferricyanide Solutions to Fish, and Determination of the Cause of Mortality

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2419 37145_Toxicity_of_Ferro- _and_Ferricyanide_Solutions_to_Fish_and_D etermination_of_the_Cause_of_Mortality

“The investigation of the causes of a fish kill in waters containing ferro- and ferricyanide at concentrations far under those generally accepted as non-lethal have shown these low concentrations to be lethal due to photo- decomposition and release of the cyanide ion. Experimental data place the toxic level of these compounds, under similar conditions of light intensity, at a concentration between 1 and 2 p.p.m. This level is assumed to vary slightly under natural conditions with latitude, period of the year, temperature, water turbulence, and interferences. Rapid development of toxicity has been demonstrated at a concentration of 2 p.p.m. of either potassium ferro- or ferricyanide.”

In 1993 Merle Spandorfer wrote : ‘…Merle Spandorfer herself contracted breast cancer after practicing Historical Photography.’

From a prudent perspective it would seem advisable to avoid Historic photographic processes altogether, or to practice the medium with the strictest safety training and following very thorough precautions and safety routines.

EPA Environmental H&S Guide for Art Departments and Schools, Pratt(wastemanagementguide) http://publicsafety.tufts.edu/ehs/files/P1003I69.pdf

Tufts

‘The most important information you can have about these processes is in this area, it could stop you becoming sensitized to the chemicals, getting sick or even save your life.Theodore Hogan makes a very relevant comment about experimenting with the limits of the materials in ‘The New Photography’, that illustrates the point well,: ‘Just remember that you may exhaust your limits long before the materials reveal theirs’. ‘Ignorance of how to safely handle the chemicals used in various printing techniques can put you out of the picture’. The chemical might still be on the shelf when you are in the grave!So a correct understanding of these materials, processes and environments to handle them in is essential.

Almost all photographic chemicals can irritate the eyes, nose, throat and skin. Exposure to some chemicals such as cyanides and solvents (Turps and mineral spirits) may cause headaches, weakness, dizziness, and a sense of confusion. Prolonged exposure with chromate’s may result in skin ulcers. Other chemicals can produce severe skin and lung burns, and if they get in your eyes, blindness (hydrochloric acid, oxalic acid, potash, silver nitrate).’

(www.alternativephotography.com)

Alfred Stieglitz in 1902. Photo: Gertrude Käsebier (Wikipedia)

page continues below, scroll down for more in-depth content

A Safer Approach to Black and White darkroom work

The most common form of darkroom photography -

B+W silver gelatine based processing and printing – is not entirely without health concerns, but can be practiced with relative safety if key safety measures are observed.

The most common concern related to B+W photography are respiratory in nature, shallow breathing and asthma can be caused from the mists given off by the chemicals. Ensure good air flow in the darkroom through the use of fans / extraction systems / open windows and take fresh air breaks during processing.

Also avoid leaving solutions uncovered. Part of the magic of B+W processing lies in watching the image emerge in the development tray, whilst rocking the tray or agitating the print with tongs. Actually, the image will appear just as well if left in the bath all by itself – it might just take a minute longer.

To protect your health and your lungs best cover all baths with transparent sheets of plexiglass or make hinged lids for each tray. There is a precedent for this approach: in commercial print processing development machines are used that are also fully enclosed, and that emit very little harmful vapors.

This method will substantially reduce the exposure to airborne fumes that may otherwise impede your breathing or even damage your lungs. Working with an enclosed chemistry will significantly reduce your exposure to airborne fumes that might otherwise impede your breathing, and in the long run damage your lung capacity. In the following sections we include extensive writings on the topic of photo processing safety from the book ‘Making Art Safely’ by Merle Spandorfer, (NY 1992), and by Michael McCann, PhD, and the Center for Safety in the Arts.

The Gum Bichromate Process

Be cautious in how you handle ammonium or potassium dichromate: It is dangerous and poisonous. This chemical can cause lesions on your tender flesh through contact and can damage your lungs by breathing it in.

In the platinotype printing process, photographers make fine-art black- and-white prints using platinum or palladium salts. Often used with platinum, palladium provides an alternative to silver.

Photo-Transfer: The safer Alternative for image transfer an a wide variety of substrates.

Van Dyke Brown

is a printing process named after Anthony van Dyck.

It involves coating a canvas with ferric ammonium citrate, tartaric acid, and silver nitrate, then exposing it to ultraviolet light. The canvas can be washed with water, and hypo to keep the solutions in place. The image created has a Van Dyke brown color when its completed, and unlike other printing methods, does not require a darkroom.

The Van Dyke brown process was patented in Germany in 1895 by Arndt and Troost. It was originally called many different names, such as sepia print or brown print. It has even been called kallitype, however that process uses ferric oxalate instead of ferric ammonium citrate.

Silver Nitrate Safety

As an oxidant, silver nitrate should be properly stored away from organic compounds. Despite its common usage in extremely low concentrations to prevent gonorrhea and control nose bleeds, silver

Mary Stieglitz-Witte: Floral Weave, 1989 photo-transfer via color laser copier.

Many artists achieve results similar to ‘Alternative Photography’ using a variety of printing methods and photo-transfer processes. These include silkscreen printing, ‘liquid light’ paint-on photo emulsions, heat transfers for inkjet or laser prints, or

paper transfer using acrylic mediums, which currently is the most popular method. Lithographic and intaglio processes can also be adapted to work nitrate is still very much toxic and corrosive. Brief exposure will not produce any immediate side effects other than the purple, brown or black stains on the skin, but upon constant exposure to high concentrations, side effects will be noticeable, which include burns.

Long-term exposure may cause eye damage. Silver nitrate is known to be a skin and eye irritant. Silver nitrate has not been thoroughly investigated for potential carcinogenic effect.

Silver nitrate is currently unregulated in water sources by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. However, if more than 1 gram of silver is accumulated in the body, a condition called argyria may develop. Argyria is a permanent cosmetic condition in which the skin and internal organs turn a blue-gray color.

Palladium and Platinum Printing

Since their introduction in 1879, palladium and platinum prints have been recognized for their permanence, tonal richness, delicacy, noble presence, and, unfortunately, for their potential adverse health effects.

These metals, when inhaled as powders or absorbed through the skin as liquids, have been associated with long-term health effects.

Some palladium salts are suspected carcinogens; platinum salts may cause a severe form of asthma known as platinosis.

‘Oasis’, Cyanotype art on stretched cotton shown at a recent art fair in New York

Fast Image Transfer with Melanie Matthews

Palladium and platinum procedures are similar. For palladium printing, the sensitizing solution is ferric oxalate plus sodium chloropalladite or palladium chloride.

For platinum prints (platinotype), potassium chloroplatinite or platinum chloride are used.

(Spandorfer)

Photochemicals in the Darkroom

by Merle Spandorfer

Photography, which has captured the imagination of amateurs and professionals for more than 150 years, can be irresistible.

The seduction lies in the

myriad possibilities inspired by aiming a lens at a subject, the simplicity of pressing the shutter release,

and the thrill of watching the image develop in the darkroom.

As both creators and viewers, our appetite for representation can be insatiable.

adapted and updated from her book ‘Making Art Safely’ NY, 1992

Merle Spandorfer: ‘Blue Mist Echo’, 1978, gum bichromate on canvas.

’I was not given suffcient information that I was working with a lung carcinogen’, I’m fully recovered, and my art has taken new directions, and working with nontoxic materials has become a top priority.

Film-based Photography, however, is not a risk-free activity; inappropriate exposure to photochemical confers significant health risks. Thus, photography offers substantial challenges to working safely.

Some photochemicals, including solvents, acids, and alkalis, are individually (and predictably) hazardous. Photographers using many different kinds of agents also also face the specter of chemical interactions with unpredictable exposures and adverse health effects.

Many photochemicals are potential irritants, sensitizers (incite allergic reactions), or both.

Follow precautionary information on labels and observe all recommendations and substitutions. Especially, observe indicators, such as ‘Caution’, ‘Danger’, and ‘Warning’.

In poorly ventilated darkrooms, processing trays containing mixtures of developers, toners, bleaches, and fixes may release gases and vapors in concentrations sufficient to cause health effects if inhaled over longer periods.

Hazardous Gases and Vapors

The following gases and vapors may be particularly hazardous:

AMMONIA

gas arises from all ammonia solutions, including washing acids, hypo eliminator, photo rinses bleach fixes, and replenishers. Ammonia irritates the eyes and respiratory tract and may cause chronic lung problems or even death.

CHLORINE

gas arises from addition of heat or acid to hypochlorite (bleach) or potassium chlorochromate (an intensifier). Chlorine gas is intensely irritating and potentially lethal.

FORMALDEHYDE

is a preservative and hardener found in stabilizers, wetting agents, final baths, Kodalith developer, prehardeners, replenishers, and retouching dyes.

Its vapors are highly irritating and may sensitize respiratory tissues. Formaldehyde is also a suspected/known carcinogen. (At the time of publishing this newly edited text, formaldehyde has been banned from many widely available products).

Frequently overlooked symptoms include shortness of breath, eye and skin irritation, headaches, dizziness, nausea, and nosebleeds. The remaining photochemical manufacturers are looking into safer replacements; for example the most recent photo-chemistry introduced processes that were/are less reliant on formaldehyde (using an ‘aldehyde insensitive’ process).

HYDROGEN SELENIDE

a sepia toner, irritates the eyes, nose, and throat. Low-level exposures can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, metallic taste, odor of garlic on the breath, dizziness, and fatigue.

NITROGEN DIOXIDE

forms from nitric acid etching and carbon arc lamps. It is highly toxic by inhalation, and symptoms include fever and chills, cough, shortness of breath, headache, vomiting, and rapid heartbeat.

Prolonged high exposure can be fatal. Chronic exposure may cause pulmonary dysfunction and symptoms of emphysema.

OZONE,

which has a sweet odor, is also released from carbon arc lamps and from photocopy machines. Ozone irritates the eyes as well as the upper and lower airways.

PHOSGENE

(Carbonyl chloride) arises from chlorinated hydrocarbons (solvents), flames, lighted cigarettes, and ultraviolet light. The odor and irritant properties are not strong enough to give warnings of hazardous concentrations. Therefore, we must learn the sources and avoid them, since phosgene severely irritates the eyes and respiratory tract.

When inhaled, phosgene decomposes in the lungs to form carbon monoxide and hydrochloric acid, which may lead to pulmonary edema or ‘water on the lungs’. Symptoms include cough, foamy sputum, and shortness of breath. Moderate exposures can cause symptoms of dryness or burning sensations in in the eyes and throat, chest pain, and shortness of breath.

SULFUR OXIDES,

especially sulfur dioxide, arise by heating or by combing acids with any compound containing sulfur, such as ammonium thiosulfate, per sulfates (reducers), sodium sulfite, sodium thiosulfate, sulfuric acid, and sulfuric acid. Sulfur dioxide gas is a powerful lung irritant that can cause chronic lung problems.

THREE ESPECIALLY HAZARDOUS GASES AND

THEIR SOURCES DESERVE SEPARATE RECOGNITION:

CARBON MONOXIDE

is oderless and therefore difficult to detect. It may arise from incomplete combustion in carbon arc lamps or may form in the body following methylene chloride exposure. In sufficient quantities, it can kill by asphyxiation (oxygen deprivation).

HYDROGEN CYANIDE is formed from heating or combining acid with cyanides (reducers), potassium ferricyanide, or thiocyanates. Cyanide poisoning has received wide press attention; its lethal potential is well known.

HYDROGEN SULFIDE (H2S)

poisoning can also be rapidly lethal. Its characteristic rotten-egg odor may not

be detected by some. For others, the smell causes olfactory fatigue, which may decrease awareness as exposure increases.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable indicator of the presence of hydrogen sulfide. Photographers should know that H2S arises from sulfide toning solutions, and by combining acids with potassium sulfide or sodium sulfide.

Low-level exposure may cause digestive and nervous system damage , and symptoms include headache, dizziness, excitation, digestive upset, and unstable gait.

Skin absorption and ingestion hazards

The Skin

The skin is also vulnerable to photochemicals, especially of one processes film and develops photographs with unprotected hands. Wear appropriate gloves when handling and mixing chemicals; use tongs to transfer photographs through the developing process.

This greatly reduces skin exposure, absorption, and irritation. Protection is critical in the presence of cuts or breaks in the skin, for even minor scrapes increase the risk of chemical dermatitis and absorption into the body.

Severe cases of dermatitis have ended careers in photography (Tell 1989). Dermatitis (chemically related) and dermatosis (occupationally related), however, can be treated with corticosteroids, but effective treatment may also require avoidance of all routes of exposure to photochemicals during the healing process.

Ingestion of toxic substances in photography should be rare, but stories persist about photographers who identify or check their solutions by taste. This may be true of the dose and duration of exposure to a substance is minimal. However, even small amounts of acid, alkalis, organic solvents, heavy metals, and other agents used in photography can cause airway or gastrointestinal irritation.

To avoid pain or discomfort of the tongue, lips, or mouth, do not identify or check the strength of photographic solutions by tasting!

Adverse health effects may also arise from exposure to the products of chemical decomposition. For example, photographic fixers have no hazardous ingredients listed in a typical materials safety data sheets, but in the small print under ‘decomposition’ sulfur dioxide, which can cause airway irritation or bronchitis, is listed as a potential hazard.

Similarly, decomposition of sulfide toners may produce hazardous amounts of hydrogen sulfide gas.

Finally, some color developing agents are suspected carcinogens. These include benzotriazole, hydroquinone, p-methylaminophenol, p-phenyl- enediamine, pyrogallol, 6-nitrobenzimidazole, potassium dichromate and ammonium dichromate powders, thiourea, and formaldehyde (Shaw and Rossol 1989).

We recommend minimizing or avoiding exposure to these agents by substituting agents not associated with the development of tumors in animals or humans. In summary, photographers must evaluate all photochemicals and the total context of the photographic process for potential health and safety hazards.

Full Site Map: a l l p a g e s / t o p i c s

Darkroom Safety and Ventilation

Many photographers maintain darkrooms at home, most often in darkrooms and kitchens. In general, hazards in home photography can be avoided with adequate space and effective ventilation.

General dilution ventilation is usually adequate for hobbyists who undertake black-and-white processing. Greater hazards associated toning, intensifying, and color processing, however, require installation of local exhaust systems. In any case, extraction is advisable also for hobbyist use, and is often quite easy to install, for instance through fitting a window with an exhaust fan.

Because the primary route of entry of photochemicals into the body is through inhalation of vapors or gases (as shown above), appropriate and adequate ventilation is the key factor to safety in photography.

Its fundamental importance cannot be overstated.

If small children are present, or if living and working space cannot be separated, the home is not an appropriate site for a darkroom. We suggest photographers share the costs of a safe workplace located elsewhere.

The Safe Studio:

Maintains effective ventilation

Maintains a source of accessible, running water

Observes local regulations governing air pollution and disposal of potentially hazardous waste

Maintains workspace sufficient to separate wet and dry areas

Provides gloves and tongues as needed

Has walls covered with acid-resistant water-base paint or fitted with plexiglass splash backs.

PHOTOGRAPHIC

PROCESSING

HAZARDS

By Michael McCann, Ph.D., C.I.H.

http://www.uic.edu/sph/glakes/harts1/HARTS_library/photohazards.txt

BLACK-AND-WHITE PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESSING

A wide variety of chemicals are used in black and white

photographic processing. Film developing is usually done in closed canisters. Print processing uses tray processing, with successive developing baths, stop baths, fixing baths, and rinse steps. Other treatments include use of hardeners, intensifiers, reducers, toners, and hypo eliminators. Photochemicals can be purchased both as ready-to-use brand name products, or they can be purchased as individual chemicals which you can mix yourself.

MIXING PHOTOCHEMICALS

Photochemicals can be bought in liquid form, which only need diluting, or powder form, which need dissolving and diluting.

Hazards

- Developer solutions and powders are often highly alkaline, and glacial acetic acid, used in making the stop bath, is also

corrosive by skin contact, inhalation and ingestion. - Developer powders are highly toxic by inhalation, and moderately toxic by skin contact, due to the alkali and

developers themselves (see Developing Baths below). The developers may cause methemoglobinemia, an acute anemia resulting from converting the iron of hemoglobin into a form that cannot transport oxygen. Fatalities and severe poisonings have resulted

from ingestion of concentrated developer solutions. Precautions

- Use liquid chemistry whenever possible, rather than mixing

developing powders. Pregnant women, in particular, should not be exposed to powdered developer.

- Use liquid chemistry whenever possible, rather than mixing

- When mixing powdered developers, use a glove box (a cardboard

box with glass or plexiglas top, and two holes in the sides for hands and arms), local exhaust ventilation, or wear a NIOSH-approved toxic dust respirator. In any case, there should be dilution ventilation (e.g. window exhaust fan) if no local exhaust ventilation is provided. - Wear gloves, goggles and protective apron when mixing concentrated photochemicals. Always add any acid to water, never

the reverse. - An eyewash fountain and emergency shower facilities should be

available where the photochemicals are mixed due to the corrosive alkali in developers, and because of the glacial acetic acid. In case of skin contact, rinse with lots of water. In case of eye contact, rinse for at least 15-20 minutes and call a physician. - Store concentrated acids and other corrosive chemicals on low shelves so as to reduce the chance of face or eye damage in case of breakage and splashing.

- Do not store photographic solutions in glass containers. 7. Label all solutions carefully so as not to ingest solutions accidently. Make sure that children do not have access to the developing baths and other photographic chemicals.

DEVELOPING BATHS

The most commonly used developers are hydroquinone, monomethyl para-aminophenol sulfate, and phenidone. Several other developers are used for special purposes. Other common components of developing baths include an accelerator, often sodium carbonate or borax, sodium sulfite as a preservative, and potassium bromide as a restrainer or antifogging agent.

Hazards

- Developers are skin and eye irritants, and in many cases strong sensitizers. Monomethyl-p-aminophenol sulfate creates many skin problems, and allergies to it are frequent (although this is thought to be due to the presence of para-phenylene diamine as a contaminant). Hydroquinone can cause depigmentation and eye injury after five or more years of repeated exposure, and

is a mutagen. Some developers also can be absorbed through the skin to cause severe poisoning (e.g., catechol, pyrogallic acid). Phenidone is only sightly toxic by skin contact. - Most developers are moderately to highly toxic by ingestion,

with ingestion of less than one tablespoon of compounds such as monomethyl-p-aminophenol sulfate, hydroquinone, or pyrocatechol being possibly fatal for adults. This might pose a particular hazard for home photographers with small children. Symptoms include ringing in the ears (tinnitus), nausea, dizziness, muscular twitching, increased respiration, headache, cyanosis (turning blue from lack of oxygen) due to methemoglobinemia, delirium, and coma. With some developers, convulsions also can occur. - Para-phenylene diamine and some of its derivatives are highly toxic by skin contact, inhalation, and ingestion. They cause very severe skin allergies and can be absorbed through the skin.

- Sodium hydroxide, sodium carbonate, and other alkalis used as accelerators are highly corrosive by skin contact or ingestion. This is a particular problem with the pure alkali or with concentrated stock solutions.

- Potassium bromide is moderately toxic by inhalation or ingestion and slightly toxic by skin contact. Symptoms of systemic poisoning include somnolence, depression, lack of coordination, mental confusion, hallucinations, and skin rashes. It can cause bromide poisoning in fetuses in cases of high exposure of the pregnant woman.

- Sodium sulfite is moderately toxic by ingestion or inhalation,

causing gastric upset, colic, diarrhea, circulatory problems, and central nervous system depression. It is not appreciably toxic by skin contact. If heated or allowed to stand for a long time in water or acid, it decomposes to produce sulfur dioxide, which is highly irritating by inhalation.

Precautions- See the section on Mixing Photochemicals for mixing precautions.

- Do not put your bare hands in developer baths. Use tongs instead. If developer solution splashes on your skin or eyes immediately rinse with lots of water. For eye splashes, continue rinsing for 15-20 minutes and call a physician. Eyewash fountains are important for photography darkrooms.

- See the section on Mixing Photochemicals for mixing precautions.

- Do not use para-phenylene diamine or its derivatives if at all possible.

STOP BATHS AND FIXER

Stop baths are usually weak solutions of acetic acid. Acetic acid is commonly available as pure glacial acetic acid or 28% acetic acid. Some stop baths contain potassium chrome alum as a hardener.

Fixing baths contain sodium thiosulfate (“hypo”) as the fixing agent, and sodium sulfite and sodium bisulfite as a preservative. Fixing baths also may also contain alum (potassium aluminum sulfate) as a hardener and boric acid as a buffer.

Hazards

- Acetic acid, in concentrated solutions, is highly toxic by inhalation, skin contact, and ingestion. It can cause dermatitis and ulcers, and can strongly irritate the mucous membranes. The final stop bath is only slightly hazardous by skin contact. Continual inhalation of acetic acid vapors, even from the stop bath, may cause chronic bronchitis.

- Potassium chrome alum or chrome alum (potassium chromium sulfate) is moderately toxic by skin contact and inhalation, causing dermatitis and allergies.

- In powder form, sodium thiosulfate is not significantly toxic by skin contact. By ingestion it has a purging effect on the bowels. Upon heating or long standing in solution, it can decompose to form highly toxic sulfur dioxide, which can cause chronic lung problems. Many asthmatics are particularly sensitive to sulfur dioxide.

- Sodium bisulfite decomposes to form sulfur dioxide if the fixing bath contains boric acid, or if acetic acid is

transferred to the fixing bath on the surface of the print. - Alum (potassium aluminum sulfate) is only slightly toxic. It may cause skin allergies or irritation.

- Boric acid is moderately toxic by ingestion or inhalation and slightly toxic by skin contact (unless the skin is abraded or

burned, in which case it can be highly toxic).

Precautions

- All darkrooms require good ventilation to control the level of

acetic acid vapors and sulfur dioxide gas produced in photography. Kodak recommends at least 10 air changes per hour, or 170 cfm for darkrooms and automatic processors. I recommend using the larger of the two ventilation rates. The exhaust duct opening should preferably be located behind and just above the stop bath and fixer trays. The exhaust should not be recirculated. For group darkrooms, the amount of dilution ventilation should be 170 cfm times the number of fixer trays.

Make sure that an adequate source of replacement air is provided. This can be achieved without light leakage by use of light traps. Ducting used with local exhaust systems should prevent light leakage from the exhaust outlet.

- Wear gloves and goggles.

- Cover all baths when not in use to prevent evaporation or

release of toxic vapors and gases.

- Cover all baths when not in use to prevent evaporation or

INTENSIFIERS AND REDUCERS

A common after-treatment of negatives (and occasionally prints)is either intensification or reduction. Common intensifiers include hydrochloric acid and potassium dichromate, or potassium chlorochromate. Mercuric chloride followed by ammonia or sodium sulfite, Monckhoven’s intensifier consisting of a mercuric

salt bleach followed by a silver nitrate/potassium cyanide solution, mercuric iodide/sodium sulfite, and uranium nitrate are older, now discarded, intensifiers.

Reduction of negatives is usually done with Farmer’s reducer, consisting of potassium ferricyanide and hypo. Reduction has also be done historically with iodine/potassium cyanide, ammonium persulfate, and potassium permanganate/sulfuric acid.

Hazards

- Potassium dichromate and potassium chlorochromate are probable human carcinogens, and can cause skin allergies and ulceration. Potassium chlorochromate can release highly toxic chlorine gas if heated or if acid is added.

- Concentrated hydrochloric acid is corrosive; the diluted acid is an skin and eye irritant.

- Mercury compounds are moderately toxic by skin contact and may be absorbed through the skin. They are also highly toxic by inhalation and extremely toxic by ingestion. Uranium intensifiers are radioactive, and are especially hazardous to the kidneys.

- Sodium or potassium cyanide is extremely toxic by inhalation

and ingestion, and moderately toxic by skin contact. Adding acid to cyanide forms extremely toxic hydrogen cyanide gas which can be rapidly fatal. - Potassium ferricyanide, although only slightly toxic by itself, will release hydrogen cyanide gas if heated, if hot acid is added, or if exposed to strong ultraviolet light (e.g., carbon arcs). Cases of cyanide poisoning have occurred through treating Farmer’s reducer with acid.

- Potassium permanganate and ammonium persulfate are strong oxidizers and may cause fires or explosions in contact with solvents and other organic materials. Precautions

- Chromium intensifiers are probably the least toxic

intensifiers, even though they are probable human carcinogens. Gloves and goggles should be worn when preparing and using these intensifiers. Mix the powders in a glove box or wear a NIOSH-approved toxic dust respirator. Do not expose potassium chlorochromate to acid or heat.

- Chromium intensifiers are probably the least toxic

- Do not use mercury, cyanide or uranium intensifiers, or cyanide reducers because of their high or extreme toxicity.

- The safest reducer to use is Farmer’s reducer. Do not expose Farmer’s reducer to acid, ultraviolet light, or heat.

TONERS

Toning a print usually involves replacement of silver by

another metal, for example, gold, selenium, uranium, platinum, or iron. In some cases, the toning involves replacement of silver metal by brown silver sulfide, for example, in the various types of sulfide toners. A variety of other chemicals are also used in the toning solutions.

Hazards

- Sulfides release highly toxic hydrogen sulfide gas during

toning, or when treated with acid. - Selenium is a skin and eye irritant and can cause kidney

damage. Treatment of selenium salts with acid may release highly toxic hydrogen selenide gas. Selenium toners also give off large amounts of sulfur dioxide gas. - Gold and platinum salts are strong sensitizers and can produce allergic skin reactions and asthma, particularly

in fair-haired people. - Thiourea is a probable human carcinogen since it causes cancer in animals. Precautions

- Carry out normal precautions for handling toxic chemicals as

described in previous sections. In particular, wear gloves and goggles. Mix powders in a glove box or wear at oxic dust respirator. See also the section on mixing photochemicals.

- Carry out normal precautions for handling toxic chemicals as

- Toning solutions must be used with local exhaust ventilation (e.g. slot exhaust hood, or working on a table immediately in

front of a window with an exhaust fan at work level). - Take precautions to make sure that sulfide or selenium toners

are not contaminated with acids. For example, with two bath sulfide toners, make sure you rinse the print well after bleaching in acid solution before dipping it in the sulfide developer. - Avoid thiourea whenever possible because of its probable cancer status.

OTHER HAZARDS

Many other chemicals are also used in black and white

processing, including formaldehyde as a prehardener, a variety of oxidizing agents as hypo eliminators (e.g., hydrogen peroxide and ammonia, potassium permanganate, bleaches, and potassium persulfate), sodium sulfide to test for residual silver, silver

nitrate to test for residual hypo, solvents such as methyl chloroform and freons for film and print cleaning, and concentrated acids to clean trays.

Electrical outlets and equipment can present electrical hazards in darkrooms due to the risk of splashing water.

Hazards

- Concentrated sulfuric acid, mixed with potassium permanganate

or potassium dichromate, produces highly corrosive permanganic and chromic acids. - Hypochlorite bleaches can release highly toxic chlorine gas when acid is added, or if heated.

- Potassium persulfate and other oxidizing agents used as hypo

eliminators may cause fires when in contact with easily oxidizable materials, such as many solvents and other combustible materials. Most are also skin and eye irritants.

Precautions

- See previous sections for precautions in handling photographic

chemicals. - Cleaning acids should be handled with great care. Wear gloves, goggles and acid-proof, protective apron. Always add acid to the water when diluting.

- Do not add acid to, or heat, hypochlorite bleaches.

- Keep potassium persulfate and other strong oxidizing agents separate from flammable and easily oxidizable substances.

- Install ground fault interrupters (GFCIs) whenever electrical outlets or electrical equipment (e.g. enlargers) are within six

feet of the risk of water splashes.

COLOR PROCESSING

Color processing is much more complicated than black and white processing, and there is a wide variation in processes used by different companies. Color processing can be either done in trays or in automatic processors.

DEVELOPING BATHS

The first developer of color transparency processing usually contains monomethyl-p-aminophenol sulfate, hydroquinone, and other normal black and white developer components. Color developers contain a wide variety of chemicals including color coupling agents, penetrating solvents (such as benzyl alcohol, ethylene glycol, and ethoxydiglycol), amines, and others.

Hazards

- See the developing section of black and white processing for

the hazards of standard black and white developers. - In general, color developers are more hazardous than black and

white developers. Para-phenylene diamine, and its dimethyl and diethyl derivatives, are known to be highly toxic by skin contact and absorption, inhalation, and ingestion. They can cause very severe skin irritation, allergies and poisoning. Color developers have also been linked to lichen planus, an inflammatory skin disease characterized by reddish pimples which can spread to form rough scaly patches. Recent color developing agents such as 4-amino-N-ethyl-N-[P-methane- sulfonamidoethyl]-m-toluidine sesquisulfate monohydrate and 4-amino-3-methyl-N-ethyl-N-[,3-hydroxyethyl]-aniline sulfate are supposedly less hazardous, but still can cause skin irritation and allergies. - Most amines, including ethylene diamine, tertiary-butylamine borane, the various ethanolamines, etc. are strong sensitizers,

as well as skin and respiratory irritants. - Although many of the solvents are not very volatile at room temperature, the elevated temperatures used in color processing can increase the amount of solvent vapors in the air. The solvents are usually skin and eye irritants.

Precautions - Wear gloves and goggles when handling color developers. Wash gloves with an acid-type hand cleaner (e.g.pHisoderm (R)), and then water before removing them. According to Kodak, barrier creams are not effective in preventing sensitization due to color developers.

- Mix powders in a glove box, or wear a NIOSH-approved toxic dust respirator.

- Color processing needs more ventilation than black and white processing due to the use of solvents and other toxic components at elevated temperatures. Preferably, for tray processing, use a 3-foot slot hood exhausting 1050 cubic feet/minute (cfm). Some automatic processors can be purchased with an exhaust, which would need to be ducted to the outside.

BLEACHING, FIXING, AND OTHER STEPS

Many of the chemicals used in other steps of color processing are essentially the same as those used for black and white processing. Examples include the stop bath and fixing bath. Bleaching uses a number of chemicals, including potassium ferricyanide, potassium bromide, ammonium thiocyanate, and acids. Chemicals found in prehardeners and stabilizers include succinaldehyde and formaldehyde; neutralizers can contain hydroxylamine sulfate, acetic acid, and other acids.

Hazards

- Formaldehyde is moderately toxic by skin contact, and highly toxic by inhalation and ingestion. It is an skin, eye and respiratory irritant, and strong sensitizer, and is a human carcinogen. Formaldehyde solutions contain some methanol, which is highly toxic by ingestion.

- Succinaldehyde is similar in toxicity to formaldehyde, but is not a strong sensitizer or carcinogen.

- Hydroxylamine sulfate is a suspected teratogen in humans since it is a teratogen (causes birth defects) in animals. It is also a skin and eye irritant.

- Concentrated acids, such as glacial acetic acid, hydrobromic acid, sulfamic acid and p-toluenesulfonic acids are corrosive by skin contact, inhalation and ingestion.

- Acid solutions, if they contain sulfites or bisulfites (e.g., neutralizing solutions), can release sulfur dioxide upon standing. If acid is carried over on the negative or transparency from one step to another step containing sulfites or bisulfites, then sulfur dioxide can be formed.

- Concentrated acids, such as glacial acetic acid, hydrobromic acid, sulfamic acid and p-toluenesulfonic acids are corrosive by skin contact, inhalation and ingestion.

- Hydroxylamine sulfate is a suspected teratogen in humans since it is a teratogen (causes birth defects) in animals. It is also a skin and eye irritant.

- Potassium ferricyanide will release hydrogen cyanide gas if heated, if hot acid is added, or if exposed to strong ultraviolet radiation.

Precautions

- Local exhaust ventilation is required for mixing of chemicals

and color processing. See previous section for discussion of ventilation.

- Use premixed solutions whenever possible. For powders, use a glove box, or wear a NIOSH-approved respirator with toxic dust filters.

- Avoid color processes using formaldehyde, if possible.

- Wear gloves, goggles and protective apron when mixing and handling color processing chemicals. When diluting solutions containing concentrated acids, always add the acid to the water. An eyewash and emergency shower should be available.

- A water rinse step is recommended between acid bleach steps and fixing steps to reduce the production of sulfur dioxide gas.

- Do not add acid to solutions containing potassium ferricyanide or thiocyanate salts.

- Control the temperature carefully according to manufacturer’s recommendations to reduce emissions of toxic gases and vapors.

- Do not add acid to solutions containing potassium ferricyanide or thiocyanate salts.

- A water rinse step is recommended between acid bleach steps and fixing steps to reduce the production of sulfur dioxide gas.

- Wear gloves, goggles and protective apron when mixing and handling color processing chemicals. When diluting solutions containing concentrated acids, always add the acid to the water. An eyewash and emergency shower should be available.

DISPOSAL OF PHOTOCHEMICALS

There is considerable concern about the effect of dumping photographic chemicals and solutions down the drain. Besides direct concern about toxicity of the effluent, many photochemicals use up oxygen in the water when they under biological or chemical degradation. This lowered oxygen content can affect aquatic life.

Most municipal areas have waste treatment plants with secondary bacterial treatment systems. These plants can handle most photochemicals solutions if the volumes and concentrations of contaminants are not too high. For these reasons, local sewer authorities regulate the concentrations and, often, the volume of chemicals released per day (the load) into sewer systems. The total volume of effluent includes the amount of wash water.

Septic tanks systems are more fragile, although they can handle a certain amount of waste photographic effluents, if they are not too toxic to the bacteria and if too much is not released into the septic system at one time.

The following recommendations are for disposing small volumes of photographic solutions daily.

Recommendations

- Old or unused concentrated photographic chemical solutions, toning solutions, ferricyanide solutions, chromium solutions, color processing solutions containing high concentrations of solvents, and non-silver solutions should be treated as hazardous waste. A licensed waste disposal service should be contacted for proper disposal. Unused materials may be recycled by donating to arts organizations or, in some cases, schools, as an alternative.

- Contact your local sewer authority for information about disposing of your photographic solutions.

- Most small-scale photographic processing will not exceed effluent regulations. If your total load (volume/day) is within regulated amounts, but the concentrations of particular chemicals in a bath too high, then you can use a holding tank large enough to hold the process wash water and processing solutions. Then the effluent can be slowly released into the sewer system. The holding tank should be kept covered, and some dilution ventilation provided.

- Alkaline developer solutions should be neutralized first before being poured down the drain. This can be done with the stop bath or citric acid, using pH paper to tell when the solution has been neutralized (pH 7). If the developer contains sodium sulfite or bisulfite, there is the hazard of producing toxic sulfur dioxide gas if the solution becomes acidic. Therefore, neutralize slowly using the pH indicator paper to tell you when to stop. The pH should not drop below 7.

- Stop bath left over from neutralization of developer can be poured down the drain, once mixed with wash water.

- Fixing baths should never be treated with acid (e.g mixing with stop bath), since they usually contain sulfites and bisulfites which will produce sulfur dioxide gas.

- Fixing baths contain large concentrations of silver

thiocyanate, well above the 5 ppm of silver ion allowed by the U.S. Clean Water Act. The regulations includes silver thiocyanate, although silver thiocyanate is not as toxic to bacteria as free silver ion, and can be handled by bacterial waste treatment plants. If large amounts of fixer waste are

produced (more than a few gallons per day), then silver recovery should be considered. For small amounts, mixing with wash water, and pouring down the drain are possible. Local authorities

should be contacted for advice.

- There are several silver recovery systems. The simplest uses steel wool or other source of iron. The iron dissolves and silver is precipitated out. The precipitated silver must be sent to a company that can recover the silver.

- Replenishment systems, where fresh solutions are added regularly to replace solutions carried out by film or paper, reduce the daily volume of solution needing disposal. Ultimately, you will have to dispose of these replenished systems, using the above guidelines.

- For septic systems, Kodak used to recommend that photographic solutions (including wash water) constitute a maximum of 1/3 of the amount of household sanitary waste going into the septic system, and not to release more than a few pints at any one time. They no longer make this recommendation since, in some areas, you need a permit to dump photographic wastes into septic systems.

- If you have large amounts of photographic solutions for disposal (but less than 200 gallons daily, including wash water), Kodak recommends building your own activated-sludge waste treatment center from 55-gallon drums (see chapter references).

- For septic systems, Kodak used to recommend that photographic solutions (including wash water) constitute a maximum of 1/3 of the amount of household sanitary waste going into the septic system, and not to release more than a few pints at any one time. They no longer make this recommendation since, in some areas, you need a permit to dump photographic wastes into septic systems.

- Replenishment systems, where fresh solutions are added regularly to replace solutions carried out by film or paper, reduce the daily volume of solution needing disposal. Ultimately, you will have to dispose of these replenished systems, using the above guidelines.

- There are several silver recovery systems. The simplest uses steel wool or other source of iron. The iron dissolves and silver is precipitated out. The precipitated silver must be sent to a company that can recover the silver.

This data sheet was adapted from the 2nd edition of Dr. McCann’s Artist Beware., Lyons and Burford (1992).

References

- Ayers, G., Zaczkowski, J. (1991). Photo Developments – A Guide to Handling Photographic Chemicals. Envisin Compliance, Bramalea, Ont.

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1986). CHOICES – Choosing the Right Silver-Recovery Method for Your Needs. Publication No. J-21. Eastman Kodak, Rochester.

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1986). Disposal and Treatment of Photographic Effluent. Publication No. J-55. Eatman Kodak, Rochester.

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1986). Disposal of Small Volumes of Photographic Processing Solutions. Publication No. J-52.

Eastman Kodak, Rochester. (discontinued)

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1987). General guidelines for ventilating photographic processing areas, CIS-58. Eastman Kodak,

Rochester.

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1979). Safe Handling of Photographic Chemicals. Publication No. J-4.. Kodak, Rochester.

- Handley, M. (1988). Photography and Your Health. Hazard Evaluation System and Information Service, California

Department of Health Services, Berkeley.

- Hodgson, M., and Parkinson, D. (1986). Respiratory disease in

a photographer. Am. J. Ind. Med. 9(4), 349-54.

- Houk C. & Hart C. (1987). Hazards in a photography lab; a cyanide incident case study. J. Chem. Educ. 64(10), A234-A236.

- Kipen, H., and Lerman, Y. (1986). Respiratory abnormalities among photographic developers: a report of three cases. Am. J.

Ind. Med. 9(4), 341-347.

- Shaw, S. D., and Rossol, M. (1991). Overexposure: Health Hazards in Photography. 2nd ed. Allworth Press, New York.

- Tell, J. (ed). (1988). Making Darkrooms Saferooms. National Press Photographers Association, Durham.

https://www.nontoxicprint.com/safetyinphotography.htm Page 30 of 37

Darkroom Safety 8/9/23, 3:31 PM

For Further Information

Written and telephoned inquiries about hazards in the arts will be answered by the Art Hazards Information Center of the Center for Safety in the Arts. Send a stamped, self-addressed envelope for a list of our many publications.

Permission to reprint this data sheet may be requested in writing from CSA. Write: Center for Safety in the Arts, 5 Beekman Street, Suite 820, New York, NY 10038. Telephone (212) 227-6220.

CSA is partially supported with public funds from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and the NYS Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Training and Education Program.

(c) Copyright Center for Safety in the Arts 1994

OSHA PPE STANDARD On April 6, 1994, the Occupational Safety and Health

Administration (OSHA) published revisions and additions to portions of the general industry safety standard concerning personal protective equipment (PPE). The standard is effective July 5, 1994. Relevant personal protective equipment include eye, face, foot, head and hand protection.

- Tell, J. (ed). (1988). Making Darkrooms Saferooms. National Press Photographers Association, Durham.

- Shaw, S. D., and Rossol, M. (1991). Overexposure: Health Hazards in Photography. 2nd ed. Allworth Press, New York.

- Kipen, H., and Lerman, Y. (1986). Respiratory abnormalities among photographic developers: a report of three cases. Am. J.

Ind. Med. 9(4), 341-347.

- Houk C. & Hart C. (1987). Hazards in a photography lab; a cyanide incident case study. J. Chem. Educ. 64(10), A234-A236.

- Hodgson, M., and Parkinson, D. (1986). Respiratory disease in

a photographer. Am. J. Ind. Med. 9(4), 349-54.

- Handley, M. (1988). Photography and Your Health. Hazard Evaluation System and Information Service, California

Department of Health Services, Berkeley.

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1979). Safe Handling of Photographic Chemicals. Publication No. J-4.. Kodak, Rochester.

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1987). General guidelines for ventilating photographic processing areas, CIS-58. Eastman Kodak,

Rochester.

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1986). Disposal of Small Volumes of Photographic Processing Solutions. Publication No. J-52.

Eastman Kodak, Rochester. (discontinued)

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1986). Disposal and Treatment of Photographic Effluent. Publication No. J-55. Eatman Kodak, Rochester.

- Eastman Kodak Co. (1986). CHOICES – Choosing the Right Silver-Recovery Method for Your Needs. Publication No. J-21. Eastman Kodak, Rochester.

Revisions and additions include:

- General Requirements (1910.132) – A certified hazard assessment must be conducted by the employer to determine and select needed PPE. The PPE must be selected, fitted, and the worker provided with training.

The worker must demonstrate an understanding of need, usage, maintenance, and limitations of PPE. This training must be certified.

- Eye and Face Protection (1910.133) – The new criteria for protective eye and face devices will comply with ANSI Z87.1-1989. Eye and face protection must be provided for flying particles, molten metal, chemicals vapors, radiation and more. Corrective eye prescriptions shall be either worn under the PPE, or incorporated in PPE design. A chart detailing the minimum filter shade protection numbers for various processes is provided.

- Head Protection (1910.135) – Head protection must be in compliance or as effective as the ANSI Safety Requirements for Industrial Head Protection Z89.1-1969.

- Foot Protection (1910.136) – Protective footwear must comply with ANSI Protective Footwear Standard Z41-1991.

- Hand Protection (1910.136) – This section is new, and requires hand protection for potential absorption of hazards chemicals, abrasion, punctures, burns and more. Employers will base selection of hand protection on evaluation of task performance, condition, duration of task, and hazard identified.

- Appendix A and B are non-mandatory, but give further information on selection of PPE.

While these revisions are already in effect from July 5, OSHA has additionally given employers until October 5 for compliance with the hazard assessment and training requirements. Telephone Mr. James Foster at OSHA: (202) 219-8151 for further information.

Art Hazards News is published by the Center for Safety in the Arts, 5 Beekman Street, Suite 820, New York, NY 10038. (212) 227-6220.

Photographic Processing Hazards in Schools

By Michael McCann, Ph.D., C.I.H.

http://www.uic.edu/sph/glakes/harts1/HARTS_library/photohaz.txt

Photography and photographic processing are increasingly popular in secondary schools. This article discusses the hazards of classroom darkrooms and how to work safely.

Hazards

Many of the chemicals used in photographic processing can cause severe skin problems, and, in some cases, lung problems through inhalation of dusts and vapors. The greatest hazard usually occurs during the preparation and handling of concentrated stock solutions of the chemicals.

Simple Black and White Processing

Simple black-and-white processing includes mixing of chemicals, developing, stop bath, fixing and rinsing steps. The developer usually contains hydroquinone and Metol (monomethyl p- aminophenol sulfate), both of which can cause skin irritation and allergic reactions. Hydroquinone may also cause eye problems and is a mutagen, and therefore might be a cancer risk. Many other developers are even more toxic. Developers are also toxic by inhalation of the powders and by ingestion, causing methemoglobinemia and cyanosis (blue lips and fingernails due to oxygen deficiency). The developers are dissolved in a strongly alkaline solution, often containing sodium hydroxide, which can cause skin irritation and burns.

The stop bath consists of a weak solution of acetic acid. Glacial acetic acid used to make up the stop bath can cause severe skin burns, and inhalation of even the dilute vapors can irritate the respiratory system. Potassium chrome alum, sometimes used as a stop hardener, contains chromium and can cause skin and nasal ulceration, and allergies.

The fixer often contains sodium sulfite, sodium bisulfite, sodium thiosulfate (hypo), boric acid and potassium alum. Hypo and the mixture of sodium sulfite and acids produce sulfur dioxide gas, especially if acetic acid is carried over from the stop bath. Sulfur dioxide is highly irritating to the eyes and respiratory system, and asthmatics are often very sensitive to it. Potassium alum, a hardener, is a weak sensitizer and may cause some skin irritation or dermatitis.

Advanced Black and White Processing

Intensification or bleaching, reduction, and toning are advanced processes in black and white processing.

Many intensifiers (bleaches) can be very dangerous. The common two-component chrome intensifiers contain potassium dichromate and hydrochloric acid. The separate components can cause burns, and the mixture produces chromic acid. Its vapors are very corrosive and may cause lung cancer. One common bleach, potassium chlorochromate also produces chlorine gas if heated or treated with acid. Handling of the powder of another intensifier, mercuric chloride, is very hazardous because of

possible mercury poisoning. Mercuric chloride is also a skin irritant and can be absorbed through the skin and should not be used.

The most common reducer, Farmer’s Reducer, contains potassium ferricyanide. Under normal conditions it is only slightly toxic. However, if it comes into contact with heat, acids or ultraviolet radiation, the extremely poisonous hydrogen cyanide gas can be released.

Many toners contain highly toxic chemicals. These include selenium, uranium, sulfide or liver of sulfur (irritating to skin and breathing passages), gold and platinum (allergies), and oxalic acid (corrosive). Sulfide or brown toners also produce highly toxic hydrogen sulfide gas, and selenium toners produce large amounts of sulfur dioxide gas.

Hardeners and stabilizers often contain formaldehyde which is poisonous, very irritating to the eyes, throat and breathing passages, and can cause dermatitis. It also causes nasal cancer in animals. Some of the solutions used to clean negatives contain harmful chlorinated hydrocarbons.

Color Processing

There are many different types of color processes using a wide variety of chemicals. In general, color processing is much more hazardous than simple black and white processing. In addition to involving many of the same chemicals that are used in black-and-white processing, color processing commonly uses many other hazardous chemicals, including dye couplers – which can cause severe skin problems, toxic organic solvents, formaldehyde, and others. In addition many color processes give off a lot more sulfur dioxide than does black and white processing.

Precautions

Choosing Materials and Processes

- Material Safety Data Sheets should be obtained on all photographic chemicals. It is particularly important to check for hazardous decomposition products in the Reactivity Section since decomposition of fixers, toners, and other chemicals are

major hazards in photography.

- Because of the hazards of photochemicals, photographic processing should be only taught at the secondary school level, and not in elementary schools.

- During pregnancy, only simple black and white processing and use of Farmer’s Reducer is recommended; dry chemicals should not be mixed due to the risk of inhalation of the hazardous powdered developing agents. Do not do toning, intensification, or color processing because of higher risks.

- Toning, intensification and color processing should not be taught, except with a few advanced students, and only if there is proper ventilation (see Ventilation section). The only reducer allowed should be potassium ferricyanide and care should be taken to avoid heating it, mixing with acid or exposing it to ultraviolet radiation.

- During pregnancy, only simple black and white processing and use of Farmer’s Reducer is recommended; dry chemicals should not be mixed due to the risk of inhalation of the hazardous powdered developing agents. Do not do toning, intensification, or color processing because of higher risks.

- Because of the hazards of photochemicals, photographic processing should be only taught at the secondary school level, and not in elementary schools.

Ventilation

- Kodak recommends at least 10 room air changes per hour of dilution ventilation for simple black and white processing, or

170 cfm of exhaust per work station or processor. * I would recommend the larger of these two exhaust rates. (Fan exhaust rate in cubic feet/minute (cfm) is calculated by multiplying the room volume in cubic feet by the number of air changers/hour, and then dividing by sixty.) The exhaust opening should be located at the rear of the sink and as close to sink level as possible. The air should be completely exhausted to the outside and not recirculated. Replacement or makeup air should enter the room behind the person working at the sink.

- Mixing of large amounts of photochemicals, toning, and color processing should have local exhaust ventilation, for example a slot exhaust hood, but not an overhead canopy hood which would draw the contaminants past the user’s face. This slot hood would have to be designed by a industrial ventilation engineer.

Without this type of ventilation, these processes should not be done.

- “General Guidelines for Ventilating Photographic Processing Areas,” CIS-58, Eastman Kodak Company (1987).

Storage and Handling

- Photographic solutions should be stored safely in clearly marked containers that are restrained so they will not fall over. Concentrates should be stored on low shelves. Do not store incompatible chemicals such as acids and Farmer’s reducer in close proximity.

- Gloves, chemical splash goggles approved by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), and a protective apron should be worn when mixing concentrated photochemical solutions to protect against skin contact.

- Preferably use liquid chemistry rather than mixing powdered developers. If the powders are used, small amounts can be mixed into a concentrated solution inside a glove box or the teacher

can do it while wearing a toxic dust respirator. A glove box consists of an ordinary cardboard box, varnished on the inside

for easy cleaning, with a glass or plexiglass top and two holes in the sides for insertion of arms. If respirators are worn, all OSHA regulations concerning a respirator program should be followed. - When diluting glacial acetic acid (or other concentrated acids), always add the acid to the water, never the reverse. 5. Tongs should be used to handle photographic prints during printing operations so that hands are never put into the developer or other baths. If skin contact does occur, the skin should be washed copiously with water and then with an acid-type skin cleanser. In case of eye contact rinse for at least 15-20 minutes and contact a physician.

- Cover trays when not in use or pour chemicals to be reused into containers, using a funnel.

- Dispose of small amounts of photographic solutions by pouring down the sink. Mixing the stop bath and developer will partially neutralize them. Do not mix the stop bath and fixer and flush with water for at least 5 minutes after pouring the stop bath before pouring the fixer. If large enough quantities are involved, silver recovery might be desirable.

Safety Devices

- All darkrooms should have eyewash fountains that connect to the water supply and do not need hands to operate. In the area where concentrated developing solutions and glacial acetic acid are mixed, there should also be an emergency shower. There should be no electric switches or electrical outlets within splash range of the shower.

- All electrical outlets and electrical equipment within 6 feet

of possible water splashes should be equipped with ground fault circuit interrupters.

Reprinted from Art Hazards News Vol. 13 No. 9, 1990. (c) copyright Center for Safety in the Arts 1990

- All electrical outlets and electrical equipment within 6 feet

of possible water splashes should be equipped with ground fault circuit interrupters.

© art-well.org 2024